At QuadrigaCX, basic governance, risk management, and controls failed to prevent this unexpected and disastrous event or allow for a timely recovery. Clearly, access controls stopped the company from running the key cryptocurrency exchange process and transacting with its customers normally.

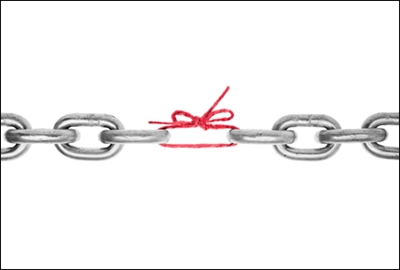

All organizations need to think about single-point-of-failure risks such as one person knowing all the key passwords to a critical process. This risk occurs when failure of one part of a system stops the entire system from working. This condition is undesirable in any system with a goal of high availability or reliability . This is what happened at QuadrigaCX, which raises important questions and lessons in three key areas.

Technology Governance, Risks, and Controls

Internal auditors should identify critical business technology governance, risks, processes, and systems to determine whether single points of failure exist. IIA Standard 1210.A3: Proficiency calls on auditors to know the business and technology they review, which they can accomplish by learning, documenting, and mapping key processes and systems. As part of that process, the auditor may analyze the process flow and identify whether certain devices or processes could become a single point of failure. For example, in some network configurations, a single router or device may serve as a key gateway. But if the one device fails, the gateway may become unavailable to users.

Likewise, a single software failure can have a calamitous impact on a business. In 2012, a failed software test at Knight Capital caused the company’s new trading system to start trading repeatedly, resulting in a $440 million loss within 45 minutes.

Information security tools or systems can become a single point of failure, too. For example, a retail company requested that all of its customers update their sign-on passwords, telling them it would give them promotional discounts and improve account security. However, the password security system became a single point of failure when suddenly too many customers logged on to update their passwords, which crashed the system. The system was not designed to handle the volume.

In addressing single points of failure, internal auditors should focus on the highest business process and technology risks. For example, Deloitte’s An Eye on the Future 2019: Hot Topics for IT Internal Audit in Financial Services report lists cybersecurity, technology transformation and change, technology resilience, and extended enterprise risks among its hot risk topics. Several of these topics apply to all organizations.

Knowing the top risks represents a start, but finding single points of failure in those areas can be challenging. Internal auditors cover program changes by testing governance and controls, but at best, auditors can only sample certain testing procedures and processes.

Disaster Recovery Backup Testing

Internal auditors should determine what recovery or backup plans are in place for the organization’s critical systems. Disaster recovery plans serve as a high-level control process to restore critical systems that were lost or disrupted. Reviewing the governance, risks, and controls over backup or disaster recovery tests allows the auditor to determine how rapidly a critical system can be recovered. The objective of recovery testing should include looking at any single points of failure such as testing for missing documents, devices, or key individuals.

Use of cloud technology and software as a service adds different factors that the auditor needs to review. For example, how frequent and how realistic are the testing plans? What mistakes or setbacks are uncovered, and more importantly, are there any single points of failure? If a critical system recovery was performed but needed a single person to provide the only passwords to transact or start the system, then the auditor or recovery team should consider this a single point of failure.

Some technology recovery plans are not completely tested or exercised because they are too complex, no resources are budgeted, or the governance is too weak. Sometimes limited recovery is considered successful.

Several years ago, during a large payroll processor’s data center disaster recovery test, an IT audit team observed that a critical system failed to restore several times. The culprit: One backup medium failed and could not be read. The disaster recovery team was able to get a new backup made but from the existing data center. This backup took more than two days to create. What would have happened if the existing data center had been unavailable or if it took weeks to restore? Would the payroll processor’s customers accept this critical service disruption?

Key Personnel

Auditors should look for key personnel or executives as a single point of failure in their audit universe or audit program. If a privileged account user, system administrator, or CEO is the person who knows the key password, and no other person or recovery process is in place, then the risk of a single point of failure increases.

To begin, internal auditors should identify who the key stakeholders — customers, vendors, or users — are for the critical systems. They should inquire and document whether any single individual performs a critical task or function and consider the single-point-of-failure risk.

Key personnel do not need to be a CEO to become a single point of failure. During a review of a large retailer’s critical key management system, an IT auditor discovered that one of the two individuals who had half of the primary encryption key had left the company. The company noticed this situation because it had not needed to generate a new key since the employee departed. If it had needed to generate a new key, a serious delay or security incident may have occurred.

Prepare for the Future

Preparing for the future, internal auditors need to continue assessing complex IT processes based on risk. The QuadrigaCX incident demonstrates that auditors need to assess possible technology single points of failure. When a single point of failure can disrupt an organization’s business or technology process, auditors need to carefully assess this threat. Ignoring it could be hazardous to the organization’s health.