For city commuters whose lives move to the rhythm of rush hour, the prospect of leaving daily gridlock behind may sound too good to be true — but it’s not at all far-fetched. Cities offer a host of advantages to residents: economic opportunity, entertainment, education, and access to advanced healthcare, to name just a few. And for businesses, the concentration of consumers and potential talent can be critical.

But time spent sitting in traffic is often significant: more than 150 hours a year in Chicago, 122 hours in Bogota, Colombia, and 156 hours in London, according to transportation analytics company INRIX’s Global Traffic Scorecard. That can discourage potential residents and present a barrier for businesses. And with the United Nations projecting that more than two-thirds of the world’s population will live in cities by 2050 — up from just over half currently — the situation is likely to get worse.

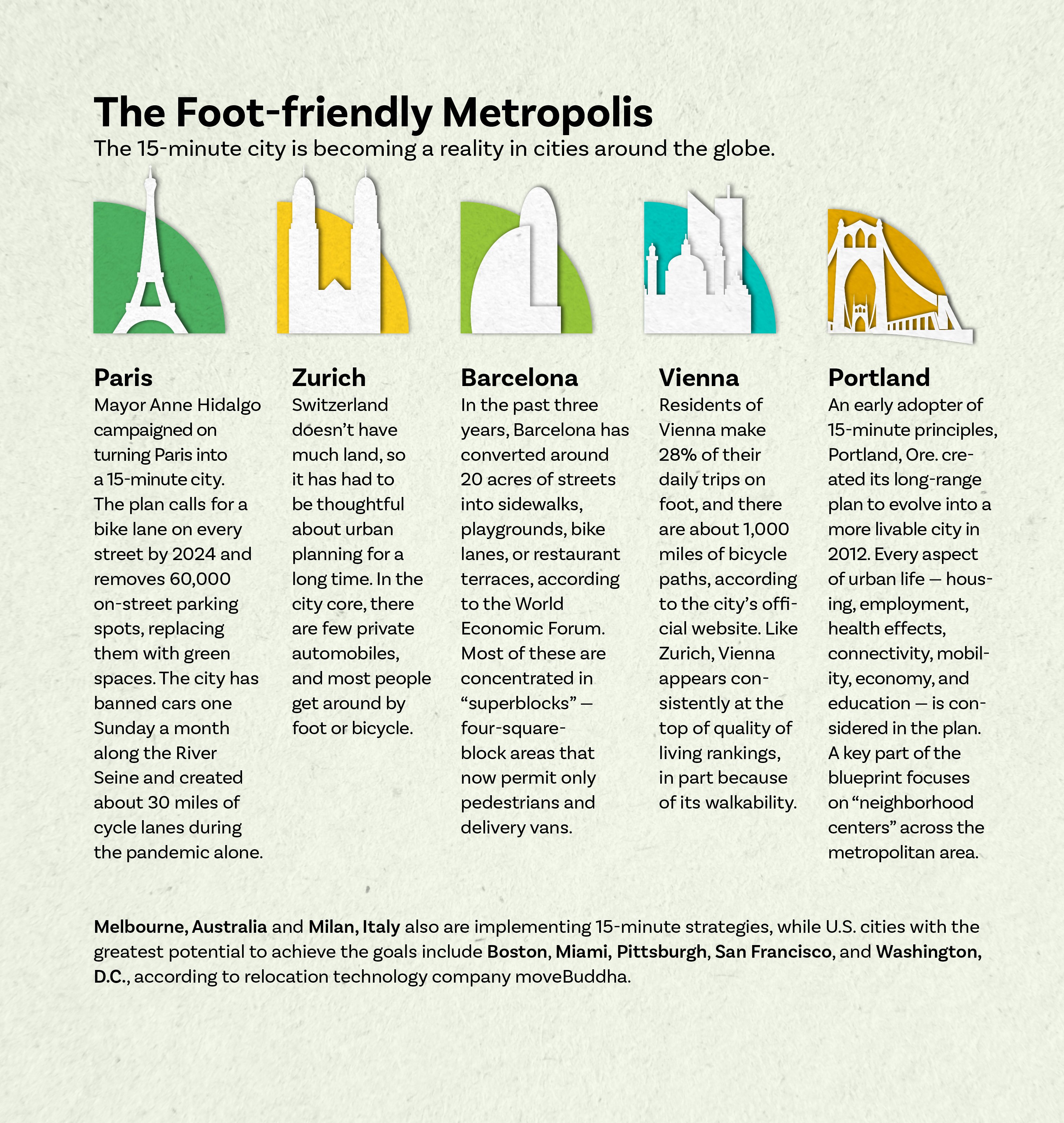

That’s in part why there is growing interest in the development of 15-minute cities. “These neighborhoods, where you don’t need a car and can easily access almost anything you might need on foot or bicycle, are very much in demand,” says Francisco Alaniz Uribe, associate professor, School of Architecture, Planning, and Landscape, and co-director of the Urban Lab, at the University of Calgary in Canada. In fact, around the world in places such as Zurich, Vienna, Paris, and Portland, Ore., they’re already becoming a reality (see “The Foot-friendly Metropolis” on this page).

More widespread adoption of the 15-minute city concept could offer numerous benefits across stakeholders, including better quality of life for residents, business opportunities for organizations, and increased revenue for municipalities. But there is a lot to consider — and ground to cover — before those benefits can be fully realized.

Reinventing the Neighborhood

The advantages of 15-minute cities to residents go far beyond spending less time in traffic, saving money on fuel, and reducing one’s carbon footprint. “In walkable places, where we live closer together, there are more of us paying for infrastructure. That means we can have a better transit system, better roads, better sidewalks, better parks, and more public places,” Alaniz says.

These quality-of-life improvements also can benefit businesses, as promoting their location near cities with such desirable features could help with recruiting and retention. Alaniz points to the desire among many younger workers to live in a walkable neighborhood, noting that some larger businesses have already located their offices in such areas. “If you look at headquarters for many big tech companies, they’re in cities like Portland or Seattle,” he says. “Google has a large office in Zurich, and Vienna is another IT hot spot. Both employers and employees stand to gain from this type of environment.”

And while Alaniz points out businesses may need to adapt some of their practices to the 15-minute city, those adaptations can come with benefits, too. For example, walkable neighborhoods tend to have more grocery stores, he says, but they are not the huge supermarkets common in suburbs. Having more, but smaller, stores could require retailers to recalibrate their business models, catering to residents in a more targeted way — and that can raise their brand profiles, and profitability, in those neighborhoods.

Existing 15-minute cities tend to support vibrant local business communities, creating opportunities for organizations to shorten supply chains by buying local. That reduces transportation costs and carbon emissions, and it also can bring access to specialized local expertise. But finding viable space for large offices in these walkable neighborhoods could prove difficult, as population density tends to drive up real estate costs. Larger companies might open neighborhood satellite offices to accommodate part-time occupancy by hybrid workers instead of having them drive to a main campus miles away.

Urban Planning Hurdles

While Vienna and Zurich have succeeded by applying 15-minute principles incrementally over decades, cities at the beginning of that journey may have significant barriers to overcome. First, zoning is at the heart of many issues walkable cities seek to address. For the 15-minute city to work, higher densities are necessary.

Regulations that restrict density and those that strictly segregate land use between commercial and residential may need to be revisited. Mixed-use development, which combines residential and commercial space in the same location, can be part of the solution.

Second, setting urban boundaries where development will be allowed and sticking to them is key. “Landowners need to participate in that conversation, because they may see it as a negative,” Alaniz says. Greenfields outside these new boundaries — especially undeveloped tracts adjacent to urban areas held by developers for future development — could lose value. “We continue to make it easy to build in the suburbs, and that’s competing with the 15-minute city concept,” he adds.

Third, significant public investment may be required. Alaniz points out that many cities were originally planned with an emphasis on cars rather than pedestrians, often resulting in narrow sidewalks and dangerous intersections to cross on foot.

Finally, cities need effective and accessible mass transit to move people longer distances. Here, Alaniz sees an opportunity for businesses to partner with local government. “Sometimes private sector companies will pay for the extension of a tram or streetcar to better connect with their development, and later the city will take over operation of the line,” he says.

Building on a Walkable Foundation

Existing neighborhoods in urban areas are often the best candidates to begin implementing 15-minute principles. “Here in Calgary, we used to have a streetcar system, and those former streetcar routes are the bones of a walkable community where there’s a mix of land usage,” he says. However, areas in the urban core, especially if they have been redeveloped, can be expensive for residents and businesses.

One solution may lie in redeveloping office buildings emptied out by the pandemic — particularly in the U.S., where barriers to 15-minute city development can be substantial. Vacancy rates for U.S. commercial buildings are high: 17.9% nationwide and reaching almost 30% in San Francisco, according to real estate firm CBRE. In New York, which has a 15.5% vacancy rate, Mayor Eric Adams announced a plan to convert empty offices to 500,000 new homes. Parts of midtown Manhattan that currently allow only offices or manufacturing spaces will be rezoned to allow mixed use. Adams says some of those new homes would be rent-restricted, to keep them affordable. While office-to-residential conversions can be expensive, the right zoning reforms, municipal support, and strategic planning could make such projects more feasible in other metropolitan areas as well.

A Potential Tipping Point

A century after it was first conceptualized by urban planner Clarence Perry, the idea of the walkable neighborhood may finally be poised to fulfill its promise. As with many big changes, it may happen more by necessity than by choice. The need for businesses to locate in areas attractive to young, skilled workers and the desire of many people to live where they can walk to the grocery store, the park, and the pub might pave the way for 15-minute cities to thrive.