Dividing the cultural environment into layers can reveal deeper truths.

To increase the value of cultural audits, internal audit must go deeper, exploring the organization's foundational characteristics.

Articles Bryant Richards, CIA, CRMA, CMA, Heather Richards, CIA, CRMA, CMA - Ed.D Jun 10, 2024

To increase the value of cultural audits, internal audit must go deeper, exploring the organization's foundational characteristics.

Bad organizational culture can bring good companies down. It’s a story that’s played out over and over in the news, enough so that audit leaders are now well aware that culture is a risk.

In thinking about risk at their own organizations, 71% of internal audit leaders rank governance and culture risk as moderate, high, or very high, according to the 2024 North American Pulse of Internal Audit. That number is up from 68% in the 2023 Pulse. And the recognition that culture is highly impactful seems to be universal: In a 2021 PwC Global Culture Survey of 3,200 leaders and employees, 67% said culture is even more important than strategy or operations.

Despite this sense of urgency and risk, Pulse reports also show that internal audit leaders have been allocating a consistent 3% to 4% of their audit plans to governance and culture since 2016. This category was the third lowest in the 2024 report for resource allocation, ahead of only sustainability/nonfinancial reporting (2%) and other risk categories that didn’t make the Pulse risk list (3%).

What’s the story? One reason for the lackluster effort may be a lack of resources, as 26% of leaders who participated in the 2024 Pulse say their budgets are insufficient. Often pressed to do more with less, nearly two-thirds of audit leaders say they integrate governance and culture considerations throughout their audit plan. Doing this can improve the quality of each review by adding more dimension — while providing greater overall coverage.

Another possible reason is that audit leaders find it challenging to justify investing more resources into culture audits. Culture audits may be seen as more resource-intensive, given the chronic and long-term impacts of culture issues compared to the acute and seemingly more pressing nature of issues like cybersecurity risk and regulatory change.

An added dimension is that auditors are not typically experts in culture. While often excellent barometers for identifying healthy versus toxic organizational behaviors, internal auditors receive very little training or practice in assessing organizational culture.

The IIA’s updated Practice Guide on Auditing Culture, to be released later this year, will provide the profession an approach tied to the Global Internal Audit Standards. Even in its current iteration, the guide explains how to efficiently incorporate culture audits into other reviews allowing, at a minimum, quick scans of critical indicators, such as unreasonable expectations, incentives misaligned with values, and an attitude of hubris. As with fraud red flags, auditors are encouraged to identify and communicate compelling evidence of significant cultural risks.

However, to increase the value of cultural audits, internal audit must go deeper, exploring the foundational characteristics of organizations that make them vulnerable to high-risk areas. Such depth requires a framework embedded with cultural expertise not typically found within the profession.

Edgar Schein, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology scholar considered by many to be the father of organizational culture, provides a framework for a deeper evaluation of culture in his book, Organizational Culture and Leadership. His organizational culture model, often referred to as the Iceberg Model, divides the cultural environment into three layers: artifacts, espoused values, and underlying beliefs. These layers can help internal audit assemble and interpret cultural evidence collected through audits and everyday observations.

Artifacts are made up of the things auditors see and hear daily. They can include the language people use, the dress code, myths and stories about departments and people, the use of technology, and visible traditions like the annual holiday party. Artifacts are easy to change, but they impact culture in the smallest of ways, if at all. An example might be a campaign focused on employee engagement: Maybe the dress code loosened up, posters with slogans appeared, free pizza was provided on Fridays, and everyone received a cool new trinket — maybe a stress ball. The only lasting remnant of the initiative is likely the addition to one’s corporate stress ball collection.

Although artifacts do little to change culture, they are easy to identify and can provide clues. Contrast the culture of a company that has a formal dress code, office sizes scaled to people’s rank and title, and the habitual use of technical acronyms — with a company that has no dress code, open spaces with movable desks, and plain-spoken language peppered with occasional profanity. The artifacts paint very different pictures of potential organizational cultures.

Espoused values are visible if one knows where to look. These items include documents where the organization pledges its values, such as mission statements, core values, charters, and contracts. Espoused values are changeable and can have some impact on culture. Given the documented nature of many of these items, they make for great audit evidence and can be the tangible focus of an action plan.

Achieving organizational alignment between espoused values and behavior is complex and difficult. Leveraging The IIA’s practice guide, internal auditors can identify mismatches between documented espoused values and significant organizational behaviors or actions, such as between core values and incentive plans.

As changes to espoused values can impact culture, these efforts are worthwhile. However, updates to documentation don’t always result in changes in behavior. For example, a department may agree to update a procedure, but then, for whatever reason, choose not to follow it.

Underlying assumptions are difficult to find and change. These beliefs are the most powerful and impactful cultural components. Underlying assumptions include the collective perceptions of how to work together, behaviors that lead to success and failure, what makes employees feel safe, and who has power and why. For example, what might be the collective beliefs of a company with a poor track record for remediating audit findings? Is it possible other departments see internal audit as an adversary? Maybe people feel safer working in a less restrictive control environment where accountability is harder to assign. Maybe internal audit is not perceived as having any authority.

Underlying assumptions are the buried treasure. Sifting through artifacts and espoused values is how to find them. These beliefs are the switches and levers that shape organizational behavior, limiting or supporting the overall control environment. At this level, internal audit is looking for cultural characteristics and the degree to which they are consistently expressed, such as how cross-department collaboration is important to success or how challenging executives in meetings can impede advancement.

Consider a toxic environment that is full of fraud and waste. The collective beliefs may include a sense of entitlement, a belief that no one is watching, and a sense that it is safer to be perceived as a perpetrator than to demonstrate integrity.

Identifying and communicating these assumptions is a familiar challenge for internal audit. Performing reviews of tone at the top and fraud requires internal auditors to identify and provide evidence for behavioral red flags. To enhance the value of culture audits, internal audit must convincingly communicate underlying assumptions and their impact on the cultural goals of the organization. Are these beliefs supportive of a resilient and high-performing culture, or are they detrimental to the organization’s goals, likely leading to toxic environments and quiet quitting?

Like other operational reviews, the process must include alignment with the organization’s objectives and mission. Unlike other reviews, internal audit will need to know or infer the organization’s cultural objectives.

Organizations seeking robust cultural insights need a more comprehensive approach, like an annual culture risk assessment. This requires a culture leader, such as the chief human resources officer, to identify the organization’s intended cultural characteristics and then map them to the organization’s mission, goals, and objectives.

Internal audit can apply Schein’s culture model throughout the organization. It can establish weightings for critical processes such as onboarding and performance appraisals — and perform departmental assessments to provide leadership with individual insights. Data from exit interviews and employee engagement surveys may provide powerful evidence. Results from the assessment could lead internal audit to add more culture-focused procedures and specific culture audits to the audit plan.

Similar to the risk assessment process, internal auditors can expect the culture risk assessment to evolve after each iteration. Collaboration with management will help identify additional valuable evidence and data collection procedures. The first iteration may result in an incomplete, but directionally useful document. As each iteration builds upon the last, auditors can expect the value to increase each year. Once the process is solidified, audit leaders should envision the potential of this process. A heatmap could be generated annually to identify risk areas in need of further exploration and remediation. The value to management grows as internal audit updates this document quarterly, providing some degree of real-time data on the organization’s cultural standing.

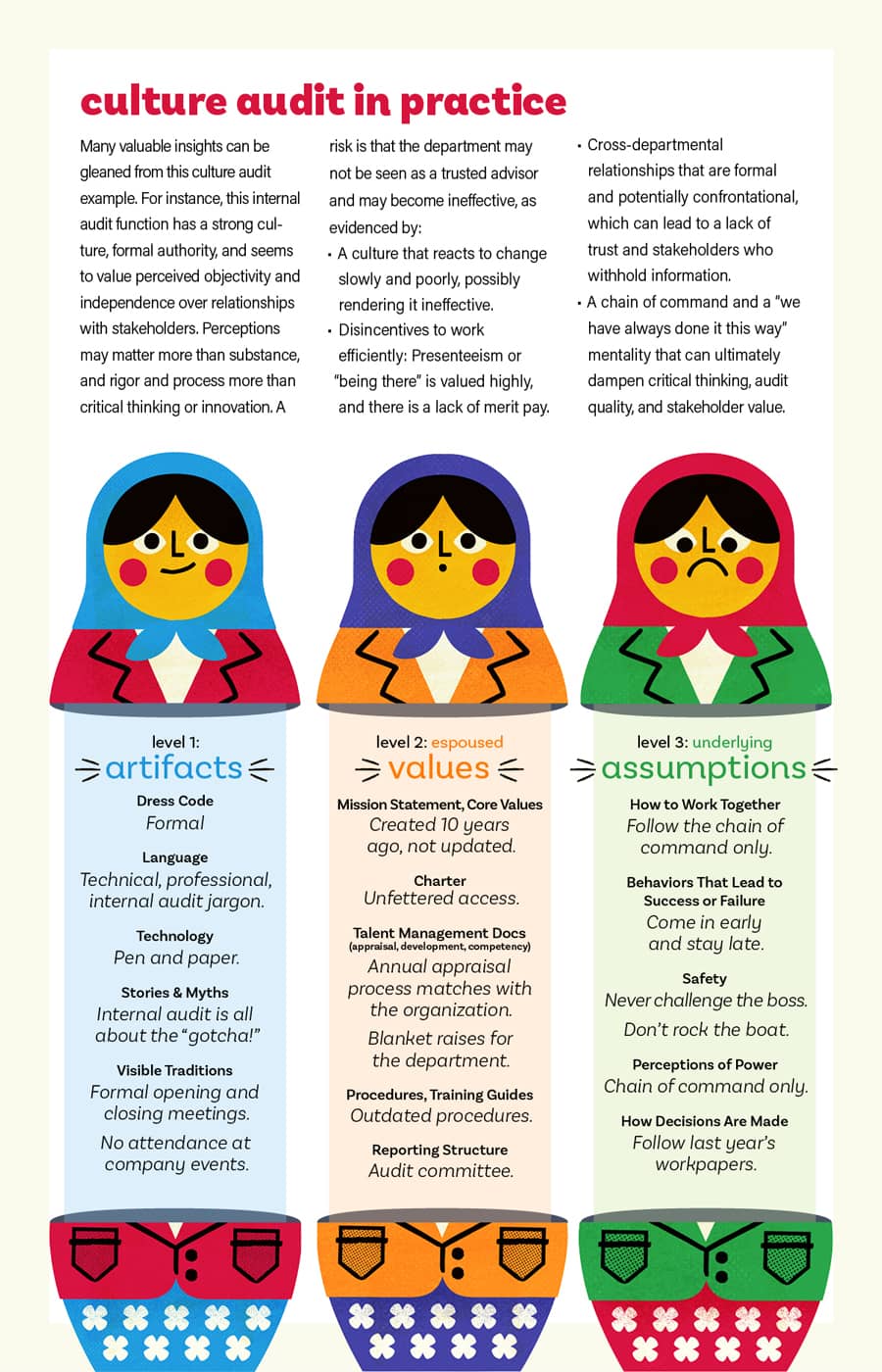

The “Culture Audit in Practice” offers an example of a culture audit using an internal audit department. Although the framework offers significant flexibility with how much to capture, what is important, and how to identify findings, internal audit can follow these basic steps:

Step 1: Identify artifacts, espoused values, and underlying assumptions and add them to the culture audit framework. There is no requirement for the number added to each category, and it is easier to start with more. For artifacts and underlying assumptions, weed out those that have less support or repetition throughout the organization.

Step 2: Assess the strength of the culture. According to Schein, the strength of a culture can be defined in terms of 1) the homogeneity and stability of group membership and 2) the length and intensity of shared experiences among the group. Internal auditors can explore data like employee tenure and turnover, diversity among employees, and challenging experiences shared such as layoffs or the launch of a new product.

Step 3: Compare the framework with organizational cultural goals. Identify mismatches.

Step 4: Identify underlying assumptions and espoused values that could contribute to red flags, such as unrealistic pressure.

With a framework aligned with organizational objectives, the profession has the capability to deliver credible and useful results. One caveat is that the seemingly abstract and personal nature of culture and related characteristics may require a new level of trust and sensitivity. CAEs should consider, for example, the potential reaction of a departmental leader when internal audit documents a possible cultural weakness on his or her team for the first time. CAEs must ensure that auditors have the credibility, confidence, and leadership support to execute this delicate and important activity in a collaborative fashion.

Imagine the impact were internal audit able to help leadership identify the elusive nobs and dials of corporate culture. Assessments could be used to prevent impending scandals and toxic behavior years before they happen. And internal audit would be seen as a trusted advisor to department leaders as they manage the most important control in the company: the culture.