The Samoa-based production team were known as the Operations Excellence Leaders across the European Chocolate Manufacturing Group, with multiple production team leaders getting promotions, awards, and even positions in other European Chocolate plants as international assignees. In fact, they were earning extra credits (and incentives, of course) by becoming trainers for other manufacturing facilities around the world.

When the internal audit team stepped in, the plant was oozing with confidence, basking in glory. Internal audit’s initial role aligned with the third line in the governance structure: to provide independent and objective assurance.

Peeling Back the Layers

Red Flag 1: SCADA vs. Reality

- Machine-level supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) and PLC logs revealed actual waste in the range of 5~8%, significantly above the reported 2%.

- Three not-required-to-run (NRR) machines were found generating waste or defects for up to six hours per day, but the production logs in their PLC were wiped clean.

What was the production team’s response?

- The PLC logs were defective and were not capturing true waste/defect.

- The NRR machines were dry run for six hours by production team leaders as a regular practice.

- Only the manual data were correct.

When asked if the production team had communicated with the equipment manufacturer regarding this alleged “machine waste recording defect,” they had no answer, of course. Moreover, there were no recent calibration logs or maintenance records for the waste-monitoring sensors.

Red Flag 2: Misaligned KPIs

Bonuses were linked directly to reported OEE figures. This misalignment had created a culture where manipulating data seemed less like a violation and more like a shortcut to recognition. Moreover, the second line didn’t have any KPI linked to accuracy of reporting. On top of that, they didn’t have the access to the machine’s PLC logs either.

Where the Three Lines Broke Down

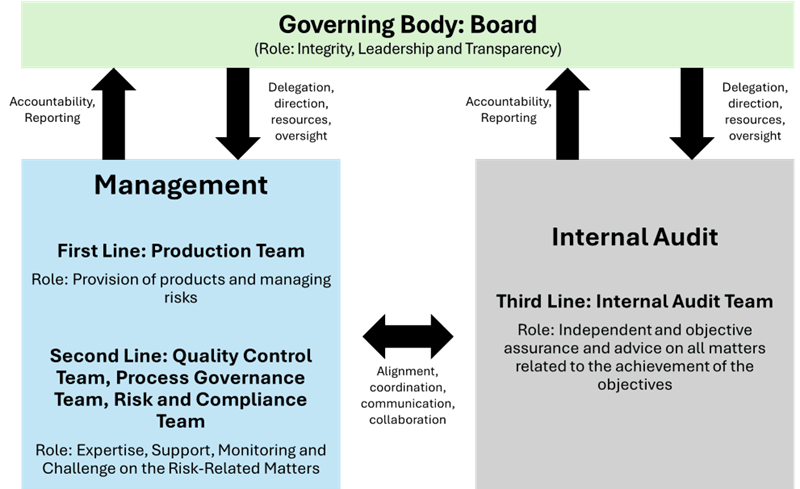

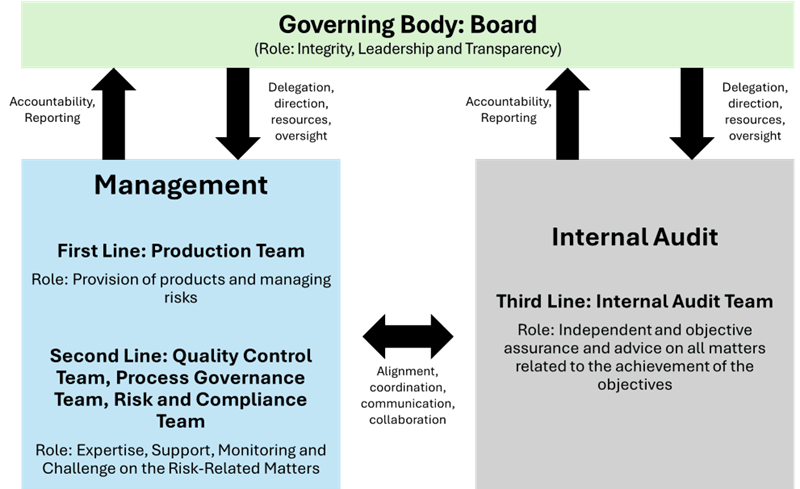

Figure 1 The Three Lines Model

Figure 1 The Three Lines Model

The first line (Production Team) focused on achieving the output goals but compromised accuracy and transparency in reporting.

The second line (QC and Process Governance) were responsible for oversight but lacked authority or accountability to detect deeper process issues.

The third line (internal audit) uncovered the gap and held up a mirror to a flawed system. What emerged was a classic failure of coordination, accountability, and culture.

Root Causes:

People:

- Performance incentives driving data tampering.

- Minimal accountability across functions.

Process:

- Fragmented systems with no unified data trail.

- No preventive controls on untracked machines.

- Oversight limited to paperwork, not process.

The Fallout

The response was swift and focused on reinforcing all three lines. The board triggered an investigation on suspicion of potential fraud, while suspending all performance-based incentives, pending results. Nine employees were found to have been involved in fraud and collusion, and disciplinary actions were taken according to labor law.

A centralized production operations management system was introduced to unify data across machines, while access controls and digital forensics were deployed to prevent future manipulation. Training was rolled out, focusing on ethics, transparency, and internal controls, with the second line empowered with oversight. Internal audit focused on continuous auditing to ensure all controls were in place.

At the end of the day, this audit served as a powerful reminder:

“What gets measured gets managed, but what gets rewarded gets manipulated.”

The audit didn’t just uncover falsified data. It uncovered a cultural blind spot — a belief that if the numbers look good, the reality behind them didn’t matter.