The NIST Cybersecurity Framework can help internal audit chase down cyber risk.

Updated in February, the framework now offers quick start guides, implementation examples, and reference tools.

Articles Christopher Kelly, DProf, FCA, PFIIA, James Hao, CPA Oct 07, 2024

Updated in February, the framework now offers quick start guides, implementation examples, and reference tools.

In the U.K. comedy, “The IT Crowd,” the IT department is relegated to the dingy basement of the otherwise glossy, steel-and-glass Reynholm Industries headquarters. The much-maligned two-man team is assigned a clueless manager and left to its own devices — as nobody understands what IT does anyway.

While clearly an exaggeration, “The IT Crowd” is not completely off base. For many business executives, board members, and even internal auditors, understanding the organization’s IT network falls into the “too-difficult” basket. But sidestepping IT is a trap. Misunderstood IT risks can result in IT departments that are underfunded, understaffed, overlooked, and vulnerable to attack by savvy cybercriminals.

Internal auditors are well-suited to bridge the knowledge gaps around IT risk and can turn to the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Cybersecurity Framework for detailed guidance. Released in 2013, the framework was designed to help critical U.S. defense and infrastructure combat cyber risk.

Because it is sector-neutral, the NIST framework also is useable across government and private sectors. An updated framework released in February offers multiple quick start guides, implementation examples, and reference tools.

Broken out into six functions — govern, identify, protect, detect, respond, and recover — the NIST framework can be used to assess the organization’s cybersecurity posture and bring vulnerabilities to light.

The six functions of the framework are intended to help organizations better understand, assess, prioritize, and communicate their cybersecurity efforts. After asessing the organization’s cybersecurity governance (see “Challenges to Cybersecurity Governance”), an auditor’s next step is to identify IT assets and risks under the NIST identify function.

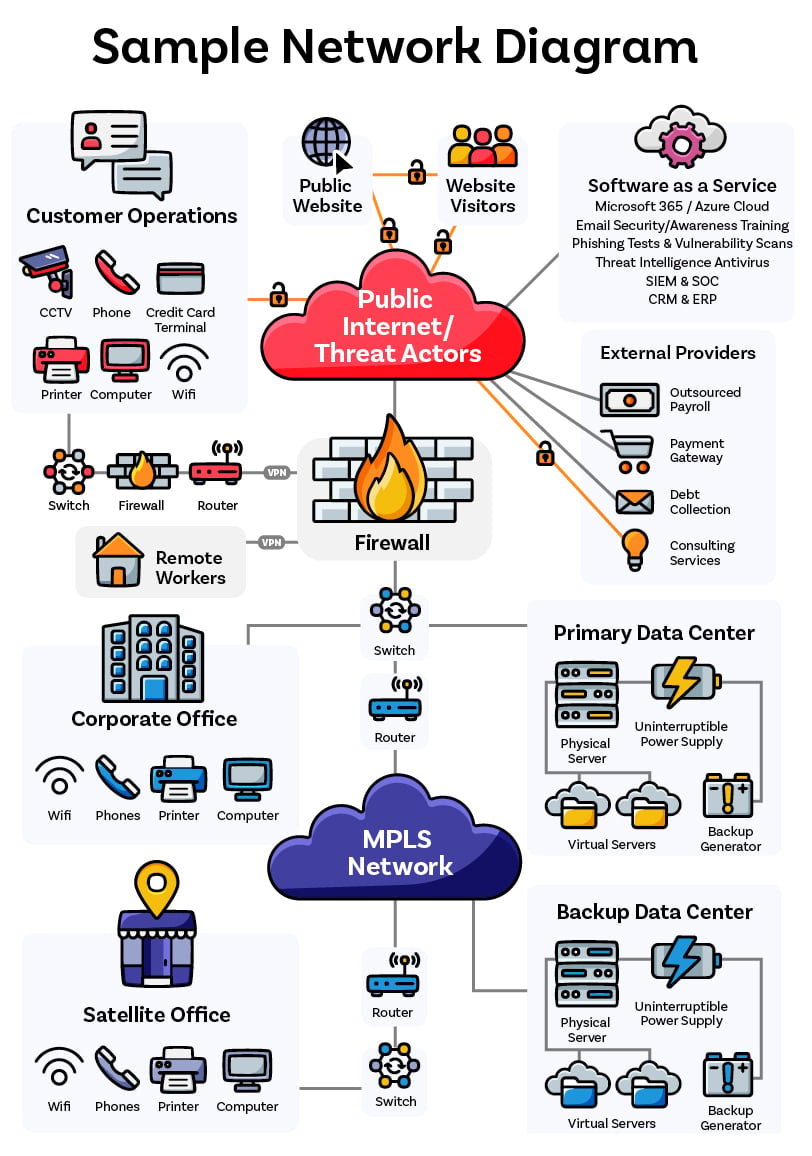

NIST’s identification controls illuminate the IT landscape, which helps internal auditors and others understand the assets, risks, and control measures within their organization. If the IT department does not have a network diagram, internal audit can develop one to use as audit’s roadmap. This guide can help audit and management visualize the tentacles of the IT network.

An IT network diagram provides a simplified overview (see “Sample Network Diagram”), showing:

Because hardware, operating systems, and business applications have a limited technical support life after which their vulnerability increases, the assets identified in the network diagram need to be managed within their expected life cycle. Once the life cycle is known, auditors can determine vulnerabilities based on whether the assets are in- or out-of-support and their latest patch status.

Microsoft tools such as System Center Configuration Manager and Windows Server Update Services act as IT asset inventories showing whether assets are in-support and patches are up to date. Other third-party tools can help identify vulnerabilities by scanning external web-facing IP addresses and internal network devices. Ideally, these will be captured in an IT risk register or vulnerabilities log. Periodic penetration tests by a “white hat” hacker can simulate what a hostile actor might be able to access. Discovered vulnerabilities will guide audit recommendations and management’s remedial actions.

NIST governance controls aim to clarify the organization’s risk appetite and regulatory obligations, and provide measures to mitigate risk and nurture a culture of cybersecurity resilience. When discussing this with the board and CEO, it can be helpful to think of risk appetite as management’s downtime tolerance of the organization’s key applications.

Applications essential to acquiring customers and earning revenue rank highest at most organizations; downtime in operational or reporting systems might be tolerated for longer. Some tolerance is unavoidable, as guaranteed zero downtime is likely cost-prohibitive.

The organization’s risk appetite will determine which actions take priority in cybersecurity measures and human resource practices. While that is straightforward intuitively, in practice it is complicated by three human behavioral challenges.

1. Workers are often better at doing than communicating. Conversely, executives are usually more capable at front-office operations than the technicalities of back-office IT. Only a few individuals will understand how to adapt management’s risk appetite into a proportionate cybersecurity resilience program.

2. Some critical applications will be managed by external suppliers, such as websites and payroll. Unless it is spelled out in service level agreements, suppliers may not be transparent about their cybersecurity risk management and may not have measures in place, such as response times, aligned to the organization’s own risk appetite.

3. As seen in recent publicized cybersecurity failures, human factors are the Achilles’ heel in most IT networks because of human susceptibility to malicious web links and social engineering, and undisciplined system administrator account practices. NIST’s governance categories help in developing the policies, procedures, accountabilities, and safeguards needed to manage cyber risk end-to-end.

NIST protection categories address safeguards around physical security, including critical servers and physical and logical user access credentials. Other protection strategies include backing up data, segmenting the network to limit damage if part of the network is compromised, and encrypting static data-at-rest stored on the organization’s servers and data-in-transit across the network’s communication links.

Physical and logical access permissions should restrict users to only what is necessary to perform their job role, with multifactor authentication (or zero trust architecture) on the most critical applications. End users, such as employees, outside contractors, or visitors, often are the weakest link because of human vulnerability, intentional wrongdoing, or social engineering by external threat actors.

All users need to be educated to these dangers, especially those with access to money, like executives and accounts payable, payroll, and treasury staff. Many organizations use a combination of training videos and email phishing tests that seek to trick users into clicking on suspicious links.

If users are reminded regularly of the latest social engineering trickery, they should be less likely to carelessly escort threat actors onto the network. Employee activity can be further controlled by network utilities such as firewalls, system logons, and user authentication domain controllers.

The most powerful users in a network are those with system administration logons with privileged access to all folders, files, emails, intellectual property, backups, access rights of all other users, and the ability to install new software. Global administrator privileges are a cyber threat actor’s golden ticket to the network. Compromised administrator credentials enable cybercriminals to engage in data theft, malware installation, and sabotage, and to encrypt the organization’s data to make it unusable. Therefore, administrator logons require maximum security measures, such as multifactor authentication, biometrics, and inactivity time-outs, to ensure they never fall into the wrong hands (see “A Guide to Continuous Authentication”).

A reliable backup strategy also falls under NIST’s recommended protection controls. With today’s cloud-based backup solutions, organizations can retain multiple backups each day, creating ever more reliable backup strategies.

NIST detection categories recommend procedures to detect anomalous and potentially hostile activity within the network, such as attempts to physically access server hardware, repeated unsuccessful login attempts, access by unauthorized endpoint devices, abnormal network traffic, or unusual system administrator action. These events would normally be quashed by the network’s suite of access and monitoring controls. But some could slip through, including unforeseen zero-day attacks for which patches have not yet been created.

Such user activity logs can be fed into a security information and event management (SIEM) system configured with likely error hypotheses to detect unusual network activity in real time. In this way, the SIEM can be fine-tuned over time, as likely threat scenarios evolve.

The SIEM’s adverse events are continuously analyzed so emerging threats can be neutralized. Current practice is to use a security operations center (SOC) to analyze the SIEM’s exceptions log, known as a SEIM-SOC solution. However, as this entails monitoring around the clock, SEIM-SOCs can be expensive. Nor will the SOC solve cyber threats, as its job is to validate and then notify the organization’s incident response team.

A cyber threat is more likely to occur outside of normal business hours. An effective incident response plan describes the decision-making hierarchy and within-hours and out-of-hours contact details of internal stakeholders and external suppliers, regulators, and insurers who need to be informed or involved in managing the incident.

At a time when management is already in crisis mode, mishandling the response could make matters worse, resulting in unnecessary costs, penalties, or reputation damage through:

NIST’s incident response controls highlight the importance of being prepared for a cyber incident to reduce the risk of incident mishandling.

To ensure an incident team of the right caliber is assembled quickly, all those with subject matter expertise should be mobilized at the outset until the dimensions of the incident are known, then stood down if not required. That ensures the team has the right skills to manage each incident’s unique characteristics.

While incident response is about fast mobilization in a crisis, NIST’s recovery function is about ensuring the organization recovers its physical assets, software applications, and business operations in a controlled way. The restoration of IT services is more complex than most types of physical assets because the disruption could result in data or applications being over-written if essential IT services are not restored in a quality-controlled sequence.

To prepare a return to operations, the organization’s subject matter experts must first validate data. The organization may need to restore applications, which could be a problem if those applications have been configured differently from their off-the-shelf standard versions. The IT team will conduct live environment checks to ensure data has not been compromised, investigate root causes of data anomalies, and take remedial action. IT should communicate its progress in restoring live operations until it confirms system stability.

The final safety net is insurance. As cyber insurance can be expensive and provide limited coverage, some organizations choose instead to rely on the control regime. In considering extortion insurance, the organization should decide whether it would pay a ransom demand, given that doing so would entail trusting the criminals to honor the agreement and could damage its reputation or encourage further attacks.

While aiming for 100% assurance is cost-prohibitive, the menace of cybercrime is unavoidably a top risk for all. The NIST Cybersecurity Framework is an adaptable roadmap. It allows management and auditors to select only the relevant categories and subcategories relative to the organization’s risk appetite. In a future increasingly shaped by evolving data analytics, machine learning, and artificial intelligence, regular cybersecurity audits are a must.

Auditing the Cybersecurity Program Certificate (Instructor-led)

Auditing the Cybersecurity Program Certificate (OnDemand)

Auditing Cybersecurity Operations: Prevention and Detection

Auditing Cyber Incident Response and Recovery